The De Stijl Movement's Echo of Struggle: Examples of Fine Art's Reflection on Social Unrest

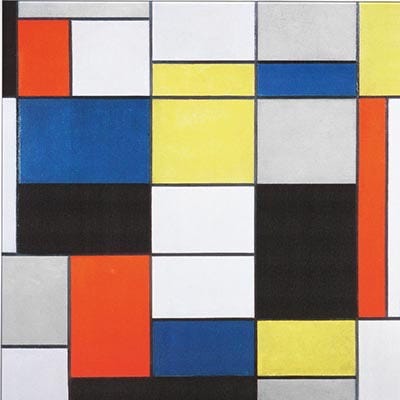

The De Stijl movement was a fine arts movement from 1917 To 1931, a formative time for modern art. This movement was created in the Netherlands by a group of Dutch artists including Piet Mondrian, Theo Van Doesberg, J.J.P. Oud, Ilya Bolotowsky, Georges Vantongerloo, Bart van der Leck, Vilmos Huszar, as well as architects Robert Van’t Hoff and Gerrit Reitveld. This style of art is described by the Museum of Modern Art as “offering a way to achieve a visual harmony in art that could provide a blueprint for restoring order and balance to everyday life”(MoMA), and in this the artists involved show the ideological power the movement was built on. The movement, lasting roughly 15 years, featured the concept of including no visually identifiable subject, but incredibly balanced paintings -with its stylistic origins lying in cubism- basic, intentional color and careful use of line; this was named by Mondrian De Stijl which, in Dutch, means “the style”. The name itself is indicative of how elemental it was intended to be viewed as- it is and was The Style.

Historical Context & World War One’s impact on the Netherlands

The Netherlands, though affected by World War One, stayed neutral but even in this minimal action, as a country they were not exempt from the suffering of the time.

The paintings that were made by the artists of the De Stijl movement brought the implicit struggle within the working class in the early 1900s to light by making his art pure abstraction with little nuance. The artist on which most art historians are focused when looking at De Stijl is Piet Mondrian. His works have become iconic in early twentieth-century cubism as well as in modern art in general. Mondrian began the De Stijl movement in 1917 while in the Netherlands, unable to leave because of the beginning of the first world war (1). At this time, Mondrian created Neo-plasticism, saying “this new plastic idea will ignore the particulars of appearance… on the contrary, it should find its expression in the abstraction of form and color, that is to say, in the straight line and the clearly defined primary color”(3). This concept is later woven into the De Stijl movement and ties into its philosophy and practice.

Reflection and acceptance of events through art

Cubism and related styles that played a part in the cultivation of the De Stijl movement are frequently used to reject one single viewpoint and rather present a subjectless piece that is seen as more impactful than that of a painting with one or more subjects. The artists involved in the De Stijl movement created a time in which the subject of art needed variation; the world needed to see a mass, united concept rather than a singled out subject. Without this lack of defined subject, the works would remain only available to those who could relate to the very narrow view of the upper class or people holding power. But with this lack of defined subject, the works grow in possible audience and meaning is derived from it by any single viewer, not only by the bourgeoisie by which academic art before this movement was aimed to be viewed.

Interpretation

A viewer can develop individual personal connections from a piece when given its context, at this point a line can be drawn from the art to the artist- then from the art to the world in which it was created. Line is either expressive or passive in its use, if we think about painting, for example, the brushstrokes can portray a tone in the piece. Is there an attempted sense of control or intended relaxed movement? What does the change in line weight mean for the composition as a whole?

Mondrian’s “Composition in Black and Grey”, for example, displays pattern with line and neutralized color, leaving a minimal composition which is meant to be more evocative of human emotion than it is of an objective description. This elaborate simplicity is due to the intricate balance in the work. The viewer’s eye does not need to evaluate more than just the grid pattern upon seeing the work- but there are countless paths the viewer can explore visually if chosen to, which makes the work accessible in being as simple or complex as the viewer decides to make it. The change in line weight throughout the grid made by this work makes the composition more elaborate and conjures up an almost mirage-like perception as the viewer follows the seemingly extemporaneous pattern of thick and thin lines. This experience creates motion and interaction with the viewer synonymous to the feeling of making eye contact with a subject of a romantic-era painting (an illusion of consciousness materializing out of the thin air that weaves through Mondrian’s shapes, no need for a subject). Mondrian says, about this lack of a defined subject, “as a pure representation of the human mind, art will express itself in an aesthetically purified, that is to say, abstract form” (3). The social interpretation of these works remains, though, that if a group of people were at a time of fear, oppression, their presence suppressed, or they are held back from progress, their art will be as liberating and vibrant as their struggle is subjugated and dark.

Explosion of Society and Art

Looking at works in the style of suprematism such as those made in Russia in roughly the same time period as the De Stijl movement, similar subject matter is expressed. A need for justice, a need for attention to cause, and a need for revolution are at the forefront of the viewer’s mind when looking at the paintings with this historical context. Art styles all rise in their time to actualize the strife of the people for whom art had not been made. Cubism- to reject the idea of a single viewpoint, branching from that movement, Neoplasticism- to promote separation from former artistic assumptions and rules, and Suprematism- to be able to communicate through consciousness and sentiment via basic and conjurable forms.

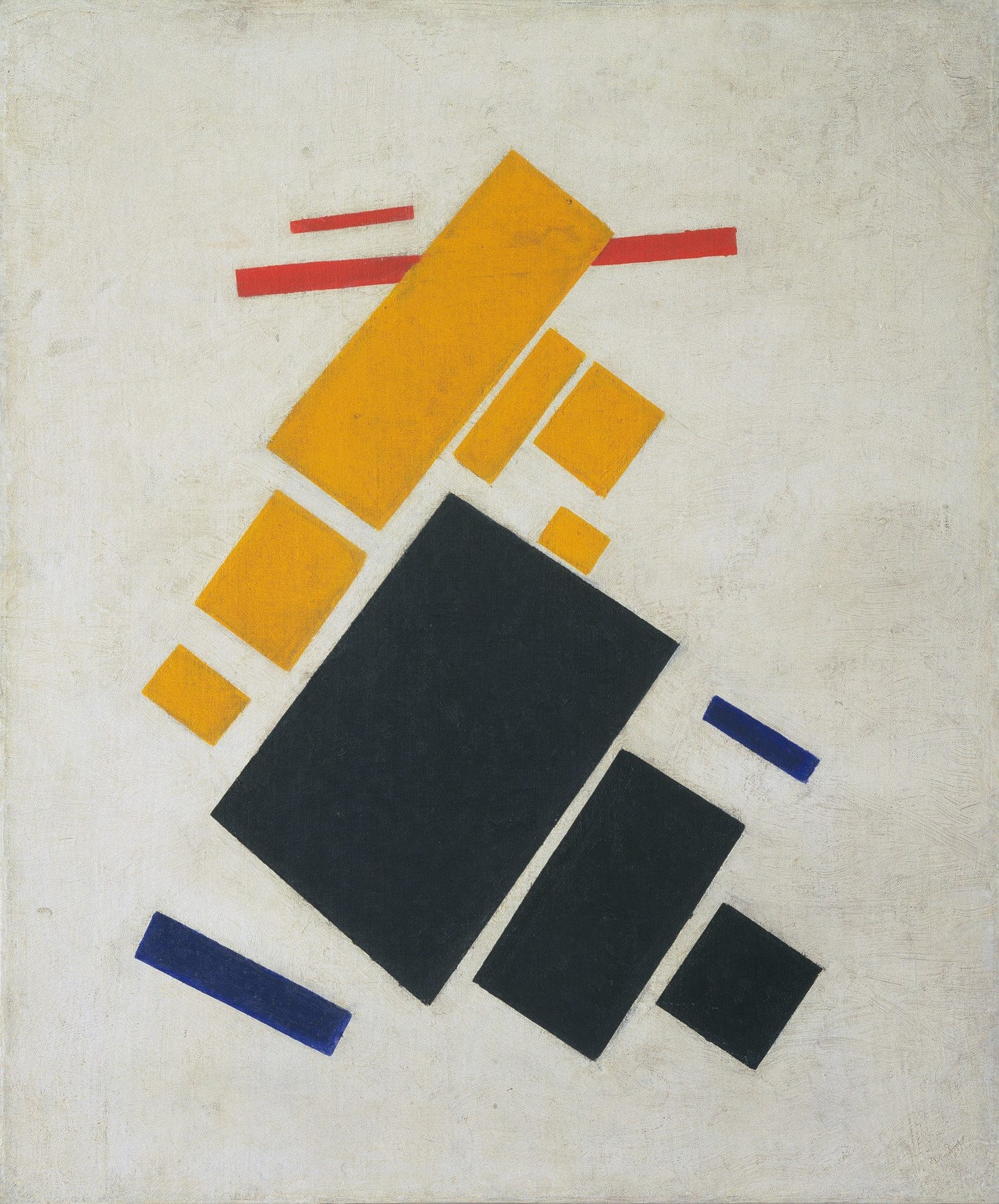

Holding a similar pull to purify and abstract his art, Kazimir Malevich, a Russian painter among those working with minimalist and geometric elements in the early 1900s, had a similar inspiration to make art that both liberated the working class and also refined form as we know it in modern art today. Malevich had the philosophy that art should not be a tool used by the rich or powerful to hold back or oppress the people. In this time, Russia’s Bolshevik revolution was reflecting that aversion to utilitarian lifestyle. Looking from Neoclassicism to Suprematism, the roots of both lie in the oppression of the working class (need for change of this status quo recognized in war or revolution). Malevich made the piece “Supremus No.58. Yellow and Black” (pictured and delineated below), specifically to show the much-needed optimism for the future of Russian society.

The core element of this rudimentary style is the availability of the art itself. When walking into any museum, there is an obvious exclusivity in the references made in fine art. Museum walls before this change would be lined solely with paintings of Jesus, angels, and general religious depictions which narrowed the scope at which viewers could relate to the art presented- considering fewer and fewer people at that time were religious or had connections to this more privileged way of life which looked up to a god when creating beauty. Artists depicted primarily religious and historical moments to which only the bourgeoisie can relate. In 1917, the Bolshevik revolution tore down the hierarchical system in Russia, conjuring revolution. This changed art, and much like their revolution- it was now made for the people with a leveled-out field for the consumption of art eliminating need for prior knowledge of previous hierarchical standards. This was a time of great change in people and their thoughts surrounding liberty, sparking these significant changes in desired works.

Analysis and Interpretation

This piece, made in 1916 by Kazmir Malevich, shows geometric shapes, almost hovering as depth is used by Malevich to suspend the shapes. In the amount of layered simplicity, the artist expresses a rise of the people; the darkness of the black panels contrasts their bordered yellow and white, creating a freeing action for the viewer. The feeling while viewing this piece is a liberating and expressive feeling- the yellow radiating full of energy in the geometric spaces, surrounded by the grounding neutrals which are accented with uplifting blues. The association with disrupting the oppressive state (reflected from the occurrences of the Bolshevik revolution) can be alluded to as these shapes seem to be moving away from a more synced former state into a fresh organization. This can almost be viewed as a slow-motion explosion of figures, layered and compressed in an orderly way to then snap from that into the composition that Malevich presents in Yellow and Black (Supremus No. 58). The common intention in Kazmir Malevich and the De Stijl movement’s art lies in their desire to eliminate a subject. As seen in the balance of this piece not needing a clear focus; this painting shows the success of building a powerful work, rich in concept, by implementing that concept of suprematism or neo-classicism.

De Stijl is the art for all the people, the appeal is not in complexity or cultural references, but rather in its simplicity and how elemental it is. It was made to be viewed and perceived by not just the bourgeois but the working class.

Things as well as stuff:

(1) “De Stijl Movement Overview.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/movement/de-stijl/.

(2) Tomassoni, Italo. Mondrian. by Italo Tomassoni. Hamlyn, 1970.

(3)“De Stijl - Concepts & Styles.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/movement/de-stijl/history-and-concepts/.

(4)“Neo-Plasticism: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/terms/66.

(5)“The Netherlands.” New Articles RSS, encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/the_netherlands.

(6)Crepaldi, Gabriele. Modern Art 1900-1945: The Age of Avant-Gardes. New York: Collins Design, 2007.

(7)Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Composition in Black and Gray.” Philadelphia Museum of Art, www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/51069.html.